On 11 October 2004 Mariano Pimentel, Ruben Resus and

Hilda Narciso submitted a communication to the Human Rights Committee,1

alleging that they were victims of violations by the Republic of the

Philippines of their rights under Article 2.3.a (right to an effective

remedy) 2

of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (which entered

into force in the Philippines on 23 January 1987).

The Petitioners

Mr. Mariano Pimentel had been arrested

in September 1972 by order of President Marcos. He was detained for a

total of four years in several detention centers, without ever being

charged. Upon return from his final period in detention, he was kidnapped

by soldiers, who beat him with rifles, broke his teeth, his arm and leg,

and dislocated his rib. He was buried up to his neck in a remote sugar

cane field and abandoned, but was subsequently rescued.

Mr. Mariano Pimentel had been arrested

in September 1972 by order of President Marcos. He was detained for a

total of four years in several detention centers, without ever being

charged. Upon return from his final period in detention, he was kidnapped

by soldiers, who beat him with rifles, broke his teeth, his arm and leg,

and dislocated his rib. He was buried up to his neck in a remote sugar

cane field and abandoned, but was subsequently rescued.

In 1974, Mr. Ruben Resus’s son, A.S., was arrested by

order of President Marcos and taken into military custody. He was tortured

during interrogation and kept in detention without ever being charged. He

disappeared in 1977.

In March 1983, Mrs. Hilda Narciso was also arrested by

order of President Marcos. She was tortured and sexually abused during her

interrogation. She was neither charged with nor convicted of any offense.

The Judgement Against Marcos in the United States of America

In April 1986, the three petitioners, together with a

class of 9,539 Philippine nationals, brought an action in the United

States of America against the estate of late Ferdinand E. Marcos, who was

then residing in Hawaii.3

On 3 February 1995, a jury at the United States District Court in Hawaii

awarded a total of US $ 1,964,005,859.90 to the 9,539 victims (or their

heirs) of torture, summary executions and disappearance. The jurors found

a consistent pattern and practice of human rights violations in the

Philippines during the regime of President Marcos from 1972 to 1986. Where

individuals were randomly selected, part of the amount of the judgment is

divided per claimant. Individuals, who were not randomly selected but are

part of the class, including the three petitioners, will receive part of

the award which was made to three classes (victims of torture, of summary

executions and of disappearance – or their heirs). However, the amounts

were not divided per claimant as it is only after collection of the

judgment amount that the United States District Court of Hawaii will

allocate amounts to each claimant.

On 3 February 1995, a jury at the United States District Court in Hawaii

awarded a total of US $ 1,964,005,859.90 to the 9,539 victims (or their

heirs) of torture, summary executions and disappearance. The jurors found

a consistent pattern and practice of human rights violations in the

Philippines during the regime of President Marcos from 1972 to 1986. Where

individuals were randomly selected, part of the amount of the judgment is

divided per claimant. Individuals, who were not randomly selected but are

part of the class, including the three petitioners, will receive part of

the award which was made to three classes (victims of torture, of summary

executions and of disappearance – or their heirs). However, the amounts

were not divided per claimant as it is only after collection of the

judgment amount that the United States District Court of Hawaii will

allocate amounts to each claimant.

On 17 December 1996, the United States Court of Appeal

for the Ninth Circuit affirmed the judgment.4

The Judgments in the Philippines

On 20 May 1997, five class members, including Ms. Narciso, filed a

complaint against the Marcos estate in the Regional Trial Court of Makati

City in the Philippines, with a view to obtaining enforcement of the

United States judgment. The defendants counter-filed a motion to dismiss

the case, claiming that the PHP 400 (US $ 7.20) paid by each plaintiff was

insufficient as the filing fee.

On 9 September 1998, the Regional Trial Court dismissed

the case, holding that the plaintiffs had failed to pay the filing fee of

PHP 472 million (US $ 8.4 million), calculated against the total amount in

dispute.

In November 1998, the petitioners filed a motion for

reconsideration before the same Court, which was denied in July 1999.

On August 1999, the same five class members filed a

motion with the Philippine Supreme Court (case Mijares et al. v. Hon.

Ranada et al.), on their own behalf and on behalf of the class, seeking a

determination that the filing fee was PHP 400 instead of PHP 472 million.

At the same time, the Philippine Supreme Court entered

a judgment for the State against the Marcos estate in a forfeiture action

and it also directed enforcement of that judgment for over US $ 650

million.

On 14 April 2005, the Supreme Court ruled on the

Mijares et al. v. Hon. Ranada et al. case affirming the plaintiff’s claim

that they should pay a filing fee of 400 PHP with respect to their

complaint to enforce the judgment of the United States District Court in

Hawaii.

Indeed, in spite of this, there has not been to date a

judgment on the enforceability of the decision of the United State

District Court of Hawaii. The issue is pending before the Regional Trial

Court of Makati City.

The Complaint to the Human Rights Committee

In 2004, when the three petitioners filed their complaint to the Human

Rights Committee, the Philippine Supreme Court had not yet issued a

judgment on their claim. Therefore, they argued that their proceedings in

the Philippines on the enforcement of the United States’ judgment had been

unreasonably prolonged and that the exorbitant filing fee amounted to a de

facto denial to their right to an effective remedy for their injuries to

obtain compensation, as recognized by article 2.3.a) of the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

The representatives of the Philippines submitted that

the communication was not admissible for failure to exhaust domestic

remedies. On the contrary, according to the petitioners, they were not

required to exhaust domestic remedies as the proceedings before the

Philippine courts had been unreasonably prolonged.

The Views of the Human Rights Committee

On 3 April 2007, the Human Rights Committee issued its

views on the case Mariano Pimentel, et al.

On the one hand, the communication was considered

inadmissible for non-exhaustion of domestic remedies as the claim

concerning the enforcement of the United States District Court of Hawaii’s

judgment was pending before the Regional Trial Court of Makati City. The

Human Rights Committee considered that the proceedings were still pending

and that the petitioners should have exhausted all domestic remedies.

Therefore, the Committee could not pronounce itself on the subject of the

enforceability of the US judgment in the Philippines and the related

decisions issued by Philippine Courts.

On the other hand, the Committee noted that since the

petitioners had brought their action before the Regional Trial Court in

1997, a period of more than eight years had elapsed before reaching a

conclusion in favor of the petitioners. In this sense, the Committee

considered that the case raised some separate issues under Article 14.1

(right to a fair trial) 5 of

the Covenant, as well as Article 2.3. The views of the Committee were

thus, focused on the proceedings concerning the amount of the filing fee

before domestic tribunals.

On the other hand, the Committee noted that since the

petitioners had brought their action before the Regional Trial Court in

1997, a period of more than eight years had elapsed before reaching a

conclusion in favor of the petitioners. In this sense, the Committee

considered that the case raised some separate issues under Article 14.1

(right to a fair trial) 5 of

the Covenant, as well as Article 2.3. The views of the Committee were

thus, focused on the proceedings concerning the amount of the filing fee

before domestic tribunals.

As to the length of those proceedings, the Committee

recalled that the right to equality before the courts, as granted by

Article 14.1, entails a number of requirements, including the condition

that the procedure before the national tribunals must be conducted

expeditiously enough so as not to compromise the principle of fairness.

Indeed, the fact that the Regional Trial Court and the

Philippine Supreme Court spent about eight years and three hearings

considering a merely subsidiary issue (determination of the filing fee)

and that the Philippines had failed to provide reasons to explain why it

took so long to consider a matter of minor complexity, amounted to a

violation of Article 14.1 in conjunction with Article 2.3 of the Covenant.

Finally, the Committee recalled that the petitioners

are entitled to an effective remedy and that therefore the Philippines is

under an obligation to ensure such adequate remedy to the authors

including compensation and prompt resolution of their case on enforcement

of the US judgment in the Philippines. Further, the Philippines is under

an obligation to ensure that similar violations do not occur in the

future.

Conclusions

The views issued by the Human Rights Committee,

although not binding in nature, represent a significant reference for all

the members of the class action against Marcos estate and for the human

rights community and civil society.

The Human Rights Committee has called on the

Philippines to respect its obligations under the International Covenant

and has explicitly mentioned the fact that the State shall provide with

compensation and prompt resolution of the case on enforcement of the US

judgment to the petitioners.

These views must now be enforced by the Philippine

tribunals and, in general, by the Philippine State. They stand as a clear

reminder of the most basic obligations the Philippine State has towards

thousands of men and women who have been awaiting justice over some of the

worst human rights violations for more than 12 years.

A prompt compensation and justice are the first steps

to undertake. However, in order to re-establish the human dignity that has

been trampled on and to build a sturdy basis for a better future, the

truth about what has happened to hundreds of disappeared people during the

Marcos regime must also be fully disclosed.

Updates

The Philippine government through the Presidential

Commission on Good Government (PCGG) has for years been contesting and

countering the claims of victims of human rights violations on the Marcos

ill-gotten wealth deposited in banks in several places in the world.

As regards the Merryll Lynch account in New York, the

PCGG argued that the claims of the victims must be dismissed from the US

court system and instead be settled in Philippine courts. The PCGG argued

further that the government owned the money because the US$2 million with

which Marcos created the account in 1972 through a dummy, a Panamanian

corporation called Arelma Foundation, Inc., was stolen from government

funds. The amount has since then grown to US$35 million.

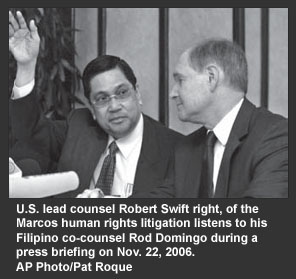

Due to the legal dispute between the Philippine

government and the victims, the Merrill Lynch firm in New York asked the

US courts to decide on who should get the money. In June 2008, the US

Supreme Court dismissed

6 the claims of the human rights victims

on the US$35 million Merrill Lynch account. With this ruling, the PCGG

proclaimed its confidence that the government will get the money in a

month’s time and this will be used “for anti-poverty programs and economic

development.” However, Atty. Robert Swift, one of the lawyers of the

victims, disputed the PCGG claim saying that “the money will revert to

Merrill Lynch and remain in the United States.” Soon after this, in July

2008, Atty. Swift filed a motion for reconsideration at the US Supreme

Court.

The Marcos ill-gotten wealth at the Swiss accounts has

a different story. The Swiss government had transferred the amount to the

Philippine government following a ruling of the Swiss Federal Court in

1998. The amount was deposited in an escrow account with the Philippine

National Bank (PNB). But still, this has not reached the victims.

In an article

7 at posted in the

Inquirer.net on 12 August 2008, it was reported that according to the

Commission on Audit (COA), the part of the Marcos ill-gotten wealth for

the human rights victims in the amount of some US$34.14 million was

missing. Based on COA’s 2007 audit report on the accounts of the PCGG, at

least US$ 34,130,468.05 or US$ 34.14 million from the Marcos Swiss

deposits which was with the Philippine National Bank (PNB) was not turned

over to the National Treasury (NT).

In a statement of Claimants 1081

8, the organization of victims

represented by its Chairperson Loretta-Pargas- Rosales, it is cited that

the group welcomes the COA findings exposing the missing US$34.14 million

from the Marcos’ ill-gotten wealth. Claimants 1081 raised its

disappointment on the government’s manner of handling the Marcos’s

ill-gotten wealth. They strongly criticized the PCGG’s failure to transfer

the amount to the NT. The organization expected that said amount would

have been transferred to the NT from the PNB after the Supreme Court had

ruled on 15 July 2003 that the money was ill-gotten. Claimants 1081 also

alleged in the same statement that the missing money was used by the PCGG

Chair Camilo Sabio, his friends and relatives for several trips to

Singapore and the US “to oppose the US$1.9 billion judgment of the class

suit that the martial law victims had won in 1995.” In view of this

development, Claimants 1081 called on the COA to order the PCGG to

reimburse the missing US$34.14 million and that the amount must be placed

in a special account to be divided among the victims of human rights

violations once the “Human Rights Compensation Bill” is enacted into law.

During the August 2008 visit to the Philippines of the

Swiss President Pascal Couchepin, President Arroyo briefed him on the

status of the Human Rights Compensation bill pending in Congress. She

assured the Swiss President that her administration “attaches great

importance to the speedy passage of the law so that human rights victims

may be justly compensated.” However, as of this writing, the bill remains

to be among the many bills due to be tabled at the Plenary Session of the

Lower House. This bill and other human rights bills are pushed aside in

favor of national issues including ‘Charter Change or Cha-cha” that seeks

to prolong the GMA administration’s stay in power beyond the May 2010

elections.

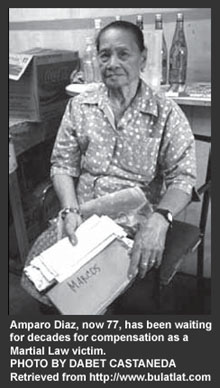

Despite the victims’ winning of the case 13 years ago,

the actual implementation of the ruling has been too circuitous and

tiring. Meanwhile, most of the close to 10,000 victims of human rights

violations or their heirs, particularly the parents of victims of enforced

disappearance, are already getting much older and physically weaker. In

fact, some of them have already died without ever seeing a ray of justice

for their loved ones.

____________________________

(Footnotes)

1 Communication No.

1320/2004.

2 Article 2.3: “Each State Party to the present Covenant

undertakes: (a) To ensure that any person whose rights or freedoms as

herein recognized are violated shall have an effective remedy,

notwithstanding that the violation has been committed by persons acting in

an official capacity”[…].

3 United States District Court in Hawaii, Estate of

Ferdinand E. Marcos Human Rights Litigation, MDL No. 840.

4 United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit,

Hilao v. Estate of Marcos, 103 F.3d 767.

5 Article 14.1: “1. All persons shall be equal before the

courts and tribunals. In the determination of any criminal charge against

him, or of his rights and obligations in a suit at law, everyone shall be

entitled to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and

impartial tribunal established by law. The press and the public may be

excluded from all or part of a trial for reasons of morals, public order (ordre

public) or national security in a democratic society, or when the interest

of the private lives of the parties so requires, or to the extent strictly

necessary in the opinion of the court in special circumstances where

publicity would prejudice the interests of justice; but any judgement

rendered in a criminal case or in a suit at law shall be made public

except where the interest of juvenile persons otherwise requires or the

proceedings concern matrimonial disputes or the guardianship of children”.

6 GMA News. TV, PCGG vows to recover all Marcos ill-gotten

wealth, posted 14 June 2008

7 Uy, Jocelyn & Avendano, Christine, COA: Escrow account

never transferred to Treasury, Inquirer.net, 12 August 2008

8 Etta Pargas-Rosales, Statement on COA Report Re Missing

$34.14 Million Ill-gotten Marcos funds, posted 15 August 2008

9 Erlinda Timbreza-Valerio conducted the research and

wrote the updates