Introduction

On 15 November 2008, the Government of Nepal, at long last, unveiled the

much eagerly and frantically awaited draft bill on Enforced Disappearances

(Charge and Punishment) Act 2008 (See Annex). The bill was formally

publicized amidst a consultation program organized by the Ministry of

Peace and Reconstruction (MoPR) in the presence of media, representatives

from selected human rights organizations and family members of victims.

Peace and Reconstruction Minister Janardan Sharma, Minister of Law,

Justice and Parliamentary Affairs Dev Gurung, Attorney General Raghav Lal

Vaidya were also present on the occasion. A short discussion program was

organized to assess the substantiality of the bill in respect to

addressing the issue of disappearances.

The

Council of Ministers approved the bill four days later, i.e. on 19

November, and the historic document is about to be tabled in the

interim legislature for endorsement. No doubt, the passage of the bill

will be vital in the impartial investigations into and subsequent exposé

of the thousands of cases of unacknowledged detention, abductions and,

above all, disappearances characteristic of the decade-long internal

conflict in the country. In the wake of this apparently delayed yet

significant step from the State, an assortment of reflexes - optimisms and

concerns, apprehensions and adumbrations – have already started and are

inevitable to surface in different forms and complexions in the days to

follow. The cliffhanger is on and it is yet to see how the plot thickens

and what credits will roll at the end.

The

Council of Ministers approved the bill four days later, i.e. on 19

November, and the historic document is about to be tabled in the

interim legislature for endorsement. No doubt, the passage of the bill

will be vital in the impartial investigations into and subsequent exposé

of the thousands of cases of unacknowledged detention, abductions and,

above all, disappearances characteristic of the decade-long internal

conflict in the country. In the wake of this apparently delayed yet

significant step from the State, an assortment of reflexes - optimisms and

concerns, apprehensions and adumbrations – have already started and are

inevitable to surface in different forms and complexions in the days to

follow. The cliffhanger is on and it is yet to see how the plot thickens

and what credits will roll at the end.

Whatever may the future consequences be, the government

definitely deserves a round of applause for its initiative. Words of

commendation have already started to drizzle in from all sectors including

victims and their families, national and international human rights

organizations, human rights defenders and other stakeholders. Though there

are some reservations from the human rights organizations vis-à-vis the

bill, the government’s step of making the bill public has certainly

imparted a glimmer of hope to family members of the victims of

disappearance.

The Bill at a Glance

In the initial analysis, the bill seems more effective, substantial

and up to the mark in comparison to the proposed draft bill on the

formation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission – which is still

thought to be below par the established international standards, although

this has been revised for four consecutive times. The key points of the

proposed bill on disappearances are as follows:

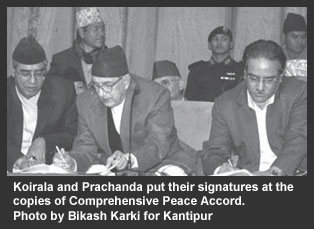

1. First of all, the bill is overtly retrospective. It

states in clear terms that the commission to be formed will focus on the

cases of disappearance between 13 February 1996 and 21 November 2006, the

day when the Seven Party Alliance government and the Maoist signed the

Comprehensive Peace Agreement.

2. The bill proposes five-year jail term and a fine to

the tune of Rs. 100,000 to the principal convict in a disappearance case.

For aides and abettors, there is a provision of half of the jail term and

the same amount of fine as for the main convict. The bill also provides

for additional two-year jail term for individuals who are found involved

in disappearing women and minors.

3. The proposed high-level independent commission to investigate into

incidents of disappearances, as per the bill, will be composed of five

members. A committee comprising of the Constituent Assembly (CA) Chairman

as the head and two incumbent ministers will recommend human rights

defenders, lawyers, sociologists, conflict experts and psychologists with

an excellent track record and at least 10 years of professional experience

as other five members of the commission.

4. The proposed commission will probe into the incidents of disappearances

during the ten-year long conflict, ascertain the guilty involved in such

acts and recommend reparation to the families of those disappeared both by

the state and non-state parties.

5. The reparation scheme to the victims’ families includes rehabilitation

measures, settlement facilities, free education and health services, skill

development trainings

and interest-free loan.

6. Besides interrogating the accused and the suspects, the proposed

commission can send directives to authorities and individuals concerned to

submit documents related to disappearance cases, ask government entities

to extend every possible help and conduct field inspection. If needed, the

commission can form separate teams of experts to gear up its activities.

7. The proposed commission will start investigations into a disappearance

case as soon as it receives complaints, ferrets out information from

sources and conducts serious investigations if it deems necessary. After

procuring relevant information and evidence, it will communicate with the

Attorney General’s Office to initiate legal action against the guilty in

such cases.

Some Concerns

As the bill is at the first draft, there are, undoubtedly, many

missing parts, which must be addressed to make it consistent with the

essence of the momentous verdict passed by the Supreme Court on 1 June

2008. The verdict, which had shaken all traditional values of evidence,

had established disappearance on the basis of situational logical

hypothesis. Besides directing the government to follow all the necessary

elements of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons

from Enforced Disappearance and the UN Criteria for a Commission of

Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances, the verdict had also stressed on clear

terms to adopt a principle that ensures, as a departure from the

traditional habeas corpus orders, against perpetrators by enacting

laws and proceeding investigations into persons being claimed as not being

detained after arrest. Likewise, the Court had decreed that any case of

perjury by security forces including responsible army offices and other

government employees should bear the criminal accountability of all cases

of illegal detention and ill-treatment to detainees.

In contradiction to such seminal backdrop, the proposed

bill on the formation of a Disappearance Commission seems incomplete in

many respects. This sounds eerie but the bill seems flawed in defining the

“disappearance” itself. The elements of disappearance as defined in the

bill (Section 2) are not in compliance with the International Convention

for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, which

regards disappearance in terms of deprivation of a person’s liberty,

whether through arrest, detention, or otherwise, by agents of state or by

persons or group of persons acting with the authorization, support or

acquiescence of the state, and which is followed by a refusal to

acknowledge that deprivation of freedom or to give information on the fate

or whereabouts of the person deprived of their liberty. Moreover, the bill

also remains silent on the cases of disappearance that have taken place

after the CPN (Maoist) came into mainstream politics in 2006 November. The

bill also lacks the doctrine of command responsibility and the rights of

the victims and family members including their right to know the truth.

The reparation policies, which forms the cornerstone of

any such commission, is not comprehensive and the provision in the bill

(Section 22) does not ensure that victims are entitled to receive

reparations as a matter of right. The definition of the victim (Section

2(b)) does not include dependents and the bill overtly fails to draw

explicit boundaries between the Disappearance Commission and the long-

proposed Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The provision of “reparation

by the perpetrator” also contradicts and deviates from the state’s

responsibility to provide appropriate reparations to the victims.

Regarding

punishment, the provision of meager five years of imprisonment and a fine

of Rs 100, 000 in the bill is far too lenient as compared to the gravity

of the crime and also compared to the international standard. To crown it

all, prosecution has been left out from the mandate of the commission plus

there is no mention of exhumation in the mandate or the objective of the

commission. The proposed selection committee to recommend for the

appointment of members and the chairperson of the commission is not

inclusive (Section 10). Further, the commission has not been granted with

subpoena powers and powers equivalent to contempt of court if there is

denial of assistance from individuals and authorities concerned. Moreover,

the bill fails to spell out clear witness protection schemes – the issues

such as providing facilities for confidential extraneous interviews,

changing of identities and relocation of victims, etc.

Regarding

punishment, the provision of meager five years of imprisonment and a fine

of Rs 100, 000 in the bill is far too lenient as compared to the gravity

of the crime and also compared to the international standard. To crown it

all, prosecution has been left out from the mandate of the commission plus

there is no mention of exhumation in the mandate or the objective of the

commission. The proposed selection committee to recommend for the

appointment of members and the chairperson of the commission is not

inclusive (Section 10). Further, the commission has not been granted with

subpoena powers and powers equivalent to contempt of court if there is

denial of assistance from individuals and authorities concerned. Moreover,

the bill fails to spell out clear witness protection schemes – the issues

such as providing facilities for confidential extraneous interviews,

changing of identities and relocation of victims, etc.

The provision in Section 26 whereby the statutory

limits for the filing of complaints has been stipulated to six months

after the enactment of the bill is awkward and inconsistent with the

Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance

which defines enforced disappearances as a continuing violation as long as

the case has not been clarified. The bill also lacks a provision to ensure

that implementation and action is taken by state authorities on

recommendations of the Commission, especially those related to

prosecutions. In addition, the provision of commutation for extending

cooperation with an investigation (Section 6(4)) is against the

established assumptions on prosecution.

Conclusion

The issue of disappearance commission is expected to feature

significantly during the Constituent Assembly Proceedings. Indeed, a

rigorous scrutiny and debate is mandatory to ensure that the bill is

consistent with the Apex Court’s Verdict and the Convention against

Enforced Disappearance particularly the provisions in the Convention which

prohibits and criminalizes the act of enforced disappearances in an

absolute manner and that obligates state parties to address and sanction

enforced disappearances. It is high time for the Constituent Assembly

members to exert pressure on the government for the ratification of the

International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced

Disappearance. The 1 June 2006 Verdict of Apex Court also holds that it is

mandatory for the government of Nepal to ratify the aforesaid Convention

for it is not a new treaty but a treaty to implement other existing human

rights treaties which Nepal is a party to.

The bill is expected to reflect that enforced

disappearances constitute a grave and continuing violation of domestic and

international law and that, when committed in the context of a widespread

or systematic attack directed against the civilian population, it

constitutes a crime against humanity. The cliffhanger is on – the victims

and their families are sitting with their fingers both on the pulse and

crossed.