From 1980 to 2000, Peru was ravaged by a bloody

internal armed conflict whose principal actors were on the one hand the

two guerrilla movements known as Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso)

and Movimiento Revolucionario Tupac Amaru (MRTA) and, on the

other, the Peruvian government, backed by self-defense groups of peasants

(rondas campesinas) and paramilitary groups created by the

intelligence service, such as the notorious Grupo Colina and

Comando Rodrigo Franco.

From 1980 to 2000, Peru was ravaged by a bloody

internal armed conflict whose principal actors were on the one hand the

two guerrilla movements known as Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso)

and Movimiento Revolucionario Tupac Amaru (MRTA) and, on the

other, the Peruvian government, backed by self-defense groups of peasants

(rondas campesinas) and paramilitary groups created by the

intelligence service, such as the notorious Grupo Colina and

Comando Rodrigo Franco.

The conflict left a heinous balance of more than 69,000

people killed (79% of whom were peasants living in remote areas of the

Andes, of indigenous origin and quechua mother tongue); 18,000

victims of enforced disappearance; 500,000 internally displaced people;

the genocide of the Asháninkas indigenous ethnic group; more than

7,000 cases of torture and rape; about 4,000 people arbitrarily detained;

6,000 children forcibly recruited; and 4,600 common graves.

On 28 July 1990, Alberto Fujimori was elected president

of Peru. Since his election, he based his fight against Sendero

Luminoso and MRTA on the widespread use of intelligence

agencies. Serious human rights abuses had been perpetrated even before

Fujimori’s presidency. However, after his election, there was an increase

in the number of grave human rights violations committed. Further, on 5

April 1992, under the pretext that it was too slow to pass an

anti-terrorism legislation, Fujimori dissolved the Congress of Peru and

abolished the Constitution. He adopted a severe anti- errorism legislation

and set up military courts where those who were suspected of being

terrorists were tried by judges “sin rostro” (whose faces were

covered in order for them not to be identified) in the absence of any

judicial guarantee.

Abimael Guzmán, the founder and leader of Sendero

Luminoso, was captured by Peruvian police in 1992. He is currently in

prison, facing a number of charges, including murder and terrorism. In

2006, together with other 11 prominent members of Sendero Luminoso,

Abimael Guzmán was sentenced to life-imprisonment for the massacre of 63

people committed in 1983. The ranks of MRTA were decimated. One of

its leaders (Víctor Polay Campos) was arrested in 1992 and is currently

serving a 35-year sentence in prison, while the other leader (Néstor Cerpa

Cartolini) was arbitrarily executed in 1997 by members of Peruvian armed

forces.

In 2000, Vladimiro Montesinos Torres, the personal

assistant of Alberto Fujimori, who acted as de facto head of

intelligence services under Fujimori’s government, was accused of bribery

of a congressman. This generated a scandal, after which both Montesinos

and Fujimori fled the country. Montesinos was later found in Venezuela and

extradited to Peru. At present, he is in a maximum security prison facing

various charges which range from drug trafficking to murder and he is

serving a 35-year sentence for corruption and illegal arms deal.

The Barrios Altos Massacre

On 3 November 1991, at approximately 11.30 p.m., 6 heavily-armed men

burst into a popular building located in the neighborhood known as

Barrios Altos in Lima, the capital of Peru. When the eruption

occurred, a party to collect funds in order to restore the building was

being held. The assailants covered their faces and obliged the people

present at the party to lie on the floor, after which, they fired

indiscriminately for about 2 minutes, killing 15 people (including an

8-year old boy) and seriously injuring another 4. The assailants fled with

the same speed with which they had arrived.

Judicial investigations and newspaper reports revealed

that those involved in the massacre worked for military intelligence and

were members of the death squad known as Grupo Colina. Purportedly,

the operation was carried out in reprisal against alleged members of

Sendero Luminoso who may have been residing in the Barrios Altos

area.

In December 1991, the Peruvian Senate set up an Investigation Committee to

clarify the events and to establish responsibilities. However, the

Senatorial Committee did not complete its investigation, because in April

1992, Fujimori dissolved the Congress and the investigation begun was

neither resumed nor were the preliminary findings of the Senatorial

Committee disclosed.

Although the events occurred in 1991, judicial authorities did not

commence a serious investigation of the incident until April 1995, when 5

army officials – members of the Grupo Colina – were accused of

being responsible for the massacre. Military courts claimed jurisdiction

in the case, alleging that it related to military officers on active

service. Before a decision could be taken on the matter of competence, on

14 June 1995, the Congress of Peru adopted Amnesty Law No. 26479, which

exonerated members of the army, police force and also civilians who had

violated human rights or taken part in such violations from 1980 to 1995

from responsibility. The effect of this law was to determine that the

judicial investigations were definitively quashed and thus, prevented the

perpetrators of the massacre from being found criminally responsible. The

few convictions of members of the security forces for human rights

violations were immediately annulled. On 28 June 1995, the Congress of

Peru adopted a second self-amnesty provision (Law No. 26492) whose effect

was to prevent judges from determining the legality or applicability of

the first self-amnesty law. Further, the second self-amnesty law expanded

the scope of the first one, granting a general amnesty to all military,

police or civilian officials who might be the subject of indictments for

human rights violations committed between 1980 and 1995, even though they

had not been formally charged.

The enactment of these 2 self-amnesty laws granted

impunity, among others, to those responsible for the Barrios Altos

massacre.

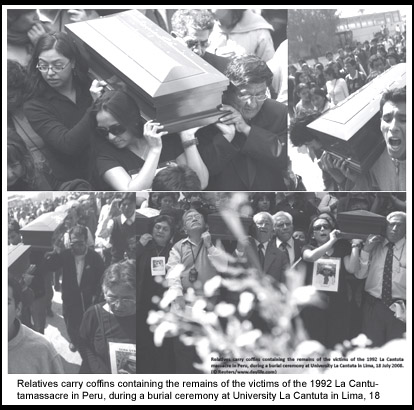

La Cantuta: Disappearances and Extrajudicial Executions

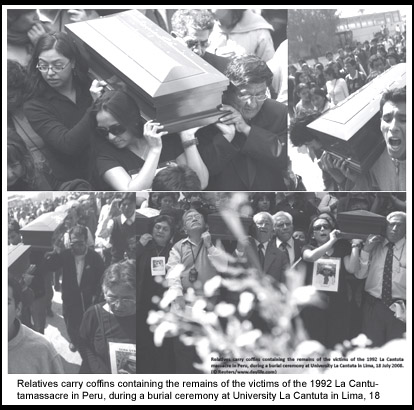

On 18 July 1992, at dawn, a group of soldiers of the

Peruvian army together with members of the Grupo Colina burst

in on the campus of the university La Cantuta and abducted 9

students and 1 professor. Allegedly, they were searching for terrorists

hiding on the university campus. The relatives of the 10 disappeared

people filed several habeas corpus writs and denounced the events

to different authorities. However, no remedy proved to be effective and

the highest authorities of the army denied that any operation had been

ever carried out at La Cantuta. Almost 1 year after the

disappearance of the 10 people, 2 common graves were located. Exhumations

led to the identification of 2 of the 10 victims. Although other mortal

remains and objects belonging to the other disappeared people were found

at the site, no exhumation or process of identification was ever carried

out. Accordingly, 8 people remain disappeared to date, as their bodies

have not been located, exhumed, identified and returned to their

relatives.

In 1994, 8 people were found guilty of homicide by a

ilitary tribunal (the same 8 people had been charged also for the

Barrios Altos massacre). The relatives were not granted access to the

proceedings. No one was investigated or charged with intellectual

responsibility for the crime. As

already mentioned, in 1995 the 2 self-amnesty laws were adopted: this

determined that all those who were awaiting trial in the La Cantuta case

were immediately relieved of their charges and those who were already

serving their sentences were freed. It was only in 2001, after the fall of

Fujimori’s regime that the Peruvian Supreme Court declared the

inapplicability of the amnesty laws and that domestic proceedings on the

events could be resumed.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission

After Fujimori fled the country, the transitional government led by

President Valentín Paniagua Morales decided to set up a Truth and

Reconciliation Commission (Comisión de Verdad y Reconciliación, CVR). The

CVR was established by decree on 2 June 2001 and mandated to investigate

and elucidate gross violations of international human rights and

humanitarian law committed during the conflict. The CVR was composed of 12

members (all Peruvian nationals, pertaining to different sectors of the

society). On 28 August 2003, the CVR released a final report 1, which

contains findings regarding thousands of abuses, including arbitrary

killings; massacres; enforced disappearances; torture and other acts of

inhumane and degrading treatment; rape and sexual violations; violations

against indigenous communities; violations against children; forced

recruitment; forced displacement and kidnappings. The CVR attempted to

ascribe responsibility to the different perpetrators concerned,

maintaining that all victims were entitled to receive reparations for the

violations suffered, aside from the identity of the perpetrators or their

family relationships.

In its final report, the CVR provided a general

overview of the root causes of the Peruvian conflict and of its peculiar

features and afterwards analyzed in depth 73 cases of outstanding human

rights violations or crimes committed by all actors involved in the

conflict. The CVR conducted investigations over those cases, collected

evidences and examined witnesses. Accordingly, it referred the 73 cases to

the Public Prosecutor, calling for the criminal indictment of those

involved. The Peruvian Ombudsman (Defensoría del Pueblo) was charged with

the monitoring of the implementation of such recommendations.

Barrios Altos and La Cantuta were among the 73 cases

investigated by the CVR 2. Regarding Barrios Altos, the

CVR affirmed that members of the Grupo Colina were

responsible for the massacre and that they were acting with

the authorization and under the direction of the highest

Peruvian authorities. The CVR found that the same people

were responsible also for La Cantuta case. In both cases,

the CVR recommended to Peruvian judicial authorities to

resume the proceedings against those allegedly responsible

(including those who ordered, solicited or induced the

commission of the crimes).

The CVR attached to its final report some general

conclusions 3, where it summarized its findings and recommendations.

Limiting the analysis to the conclusions concerning Fujimori’s

responsibilities, the CVR found that he always acted in open disregard of

democracy and, in particular, after the coup of 5 April 1992, he

intentionally determined the collapse of the rule of law. Since then, Fujimori adopted a counter-insurgency strategy based on the use of the

intelligence, aiming at selectively eliminating those suspected of being

terrorists. The CVR held that it had gathered sufficient evidence to

affirm that Fujimori, Montesinos and high rank officials of the

intelligence services were “criminally responsible for the killings,

massacres and enforced disappearances perpetrated by members of the death

squad, Grupo Colina”. 4

Although devoid of any judicial power, this finding of

the CVR was a first blow against Fujimori and represents one

of the pillars on which domestic judicial proceedings have

subsequently been based.

The Judgments of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights on the Cases

Barrios Altos and La Cantuta

The judgments on Peruvian cases rendered by the

Inter-American Court of Human Rights before and after the experience of

the CVR have proven to be of crucial importance in the struggle for

justice in Peru.

The application concerning Barrios Altos massacre was

submitted to the Court while Fujimori was still in power and he pretended

to withdraw the acknowledgement of the competence of the Court to escape

international scrutiny. Such withdrawal was rejected by the Inter-American

Court. While the case was pending before the latter, Fujimori fled the

country. The transitional government declared null the attempt of

withdrawal of the competence of the Court and recognized its international

responsibility for the violation of Articles 4 (right to life), 5 (right

to humane treatment), 8 (right to fair trial), 25 (judicial protection) in

conjunction with Article 1.1 (obligation to respect rights) of the

American Convention on Human Rights. On 14 March 2001, the Inter- American

Court rendered a landmark judgment, accepting the acknowledgement of

international responsibility and, at the same time, affirming a key

principle in the struggle against impunity.5 Referring to the enactment of

the 2 self-amnesty laws, the Court considered that:

The application concerning Barrios Altos massacre was

submitted to the Court while Fujimori was still in power and he pretended

to withdraw the acknowledgement of the competence of the Court to escape

international scrutiny. Such withdrawal was rejected by the Inter-American

Court. While the case was pending before the latter, Fujimori fled the

country. The transitional government declared null the attempt of

withdrawal of the competence of the Court and recognized its international

responsibility for the violation of Articles 4 (right to life), 5 (right

to humane treatment), 8 (right to fair trial), 25 (judicial protection) in

conjunction with Article 1.1 (obligation to respect rights) of the

American Convention on Human Rights. On 14 March 2001, the Inter- American

Court rendered a landmark judgment, accepting the acknowledgement of

international responsibility and, at the same time, affirming a key

principle in the struggle against impunity.5 Referring to the enactment of

the 2 self-amnesty laws, the Court considered that:

“[…] all amnesty provisions, provisions on prescription and the

establishment of measures designed to eliminate responsibility are

inadmissible, because they are intended to prevent the investigation and

punishment of those responsible for serious human rights violations such

as torture, extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary execution and forced

disappearance, all of them prohibited because they violate non-derogable

rights recognized by international human rights law.” 6

“[…] Self-amnesty laws lead to the defencelessness of victims and

perpetuate impunity; therefore, they are manifestly incompatible with

the aims and spirit of the Convention. This type of law precludes the

identification of the individuals who are responsible for human rights

violations, because it obstructs the investigation and access to justice

and prevents the victims and their next of kin from knowing the truth

and receiving the corresponding reparation.” 7

“Owing to the manifest incompatibility of

self-amnesty laws and the American Convention on Human Rights, the said

laws lack legal effect and may not continue to obstruct the

investigation of the grounds on which this case is based or the

identification and punishment of those responsible, nor can they have

the same or a similar impact with regard to other cases that have

occurred in Peru, where the rights established in the American

Convention have been violated.”8

Exceptionally, the judgment of the Inter-American Court was considered to

be directly applicable at domestic level and determined the loss of

effects of the 2 self-amnesty laws, allowing the resumption of criminal

proceedings for violations perpetrated during the conflict. The Court

awarded measures of reparation including pecuniary compensation, free

medical and psychological rehabilitation and scholarships. It also ordered

the establishment of a memorial monument to honor the victims and the

organization of a public event where the highest authorities of the State

were to offer their apologies and to acknowledge international

responsibility of the State.

On 29 November 2006, the Inter-American Court rendered

a judgment on La Cantuta case which was based to a large extent on the

findings of the CVR.9 The representatives of Peru partially acknowledged

the international responsibility of the State for the violation of

Articles 3 (right to juridical personality), 4 (right to life), 5 (right

to humane treatment, with regards to the material victims of the case), 7

(right to personal liberty) in conjunction with Article 1.1 (obligation to

respect rights) of the American Convention. The Court deemed it

appropriate to further clarify certain aspects of the case. First, it

found that Article 5 of the Convention had been violated not only with

regards to the direct victims of the case but also to their relatives,

whose mental and moral integrity were impaired as a direct consequence of

the events. The Court found also a violation of Articles 8 (right to a

fair trial) and 25 (right to judicial protection) in connection with

Article 1.1 of the Convention. It declared that the proceedings before the

military jurisdiction did not respect the international standards of the

fair trial and that the application of the 2 self-amnesty laws to the case

was contrary to the American Convention and, in particular, amounted to a

violation of Article 2 (domestic legal effects) of the American

Convention. While expressing appreciation for the resuming of trials

before ordinary courts on the case of La Cantuta in 2001, the Court found

that Peru had exceeded any reasonable delay. The Court pointed out that

the facts of La Cantuta were to be seen as part of a systematic practice

of enforced disappearances and extra-judiciary executions perpetrated by

State agents and paramilitary groups. This amounted to a crime against

humanity and a gross violation of ius cogens.

On 29 November 2006, the Inter-American Court rendered

a judgment on La Cantuta case which was based to a large extent on the

findings of the CVR.9 The representatives of Peru partially acknowledged

the international responsibility of the State for the violation of

Articles 3 (right to juridical personality), 4 (right to life), 5 (right

to humane treatment, with regards to the material victims of the case), 7

(right to personal liberty) in conjunction with Article 1.1 (obligation to

respect rights) of the American Convention. The Court deemed it

appropriate to further clarify certain aspects of the case. First, it

found that Article 5 of the Convention had been violated not only with

regards to the direct victims of the case but also to their relatives,

whose mental and moral integrity were impaired as a direct consequence of

the events. The Court found also a violation of Articles 8 (right to a

fair trial) and 25 (right to judicial protection) in connection with

Article 1.1 of the Convention. It declared that the proceedings before the

military jurisdiction did not respect the international standards of the

fair trial and that the application of the 2 self-amnesty laws to the case

was contrary to the American Convention and, in particular, amounted to a

violation of Article 2 (domestic legal effects) of the American

Convention. While expressing appreciation for the resuming of trials

before ordinary courts on the case of La Cantuta in 2001, the Court found

that Peru had exceeded any reasonable delay. The Court pointed out that

the facts of La Cantuta were to be seen as part of a systematic practice

of enforced disappearances and extra-judiciary executions perpetrated by

State agents and paramilitary groups. This amounted to a crime against

humanity and a gross violation of ius cogens.

It is worth noting that, while the Inter-American Court

was rendering its judgment over the case of La Cantuta, Fujimori had

already been arrested and was awaiting a decision concerning his

extradition. 10 The Court referred to such issue, noting that:

“[…] States have the duty to investigate human rights violations and to

prosecute and punish those responsible. In view of the nature and

seriousness of the events, all the more since the context of this case

is one of systematic violation of human rights, the need to eradicate

impunity reveals itself to the international community as a duty of

cooperation among states for such purpose. Access to justice constitutes

a peremptory norm of International Law and, as such, it gives rise to

the States’ erga omnes obligation to adopt all such measures as are

necessary to prevent such violations from going unpunished, whether

exercising their judicial power to apply their domestic law and

International Law to judge and eventually punish those responsible for

such events, or collaborating with other States aiming in that

direction. […]”.11

The considerations expressed by the Inter-American

Court constitute an important reference regarding the obligation of States

to judge or extradite people accused of grave human rights violations who

are in the territory under their jurisdiction.

The Court ordered Peru to investigate, judge and

sanction those found to be responsible for the violations, to pay

pecuniary compensation to the relatives of the victims, to carry out the

exhumations and to identify and deliver to the relatives of the eight

disappeared people their mortal remains, to issue an apology in a public

ceremony and to honor the memory of the victims, to provide free medical

and psychological treatment to the relatives of the victims, to publish

relevant abstracts of the judgment in the official gazette of the country

and to establish a program of education on human rights and international

humanitarian law for public officials.

The Court ordered Peru to investigate, judge and

sanction those found to be responsible for the violations, to pay

pecuniary compensation to the relatives of the victims, to carry out the

exhumations and to identify and deliver to the relatives of the eight

disappeared people their mortal remains, to issue an apology in a public

ceremony and to honor the memory of the victims, to provide free medical

and psychological treatment to the relatives of the victims, to publish

relevant abstracts of the judgment in the official gazette of the country

and to establish a program of education on human rights and international

humanitarian law for public officials.

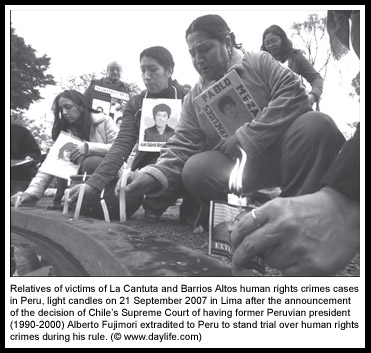

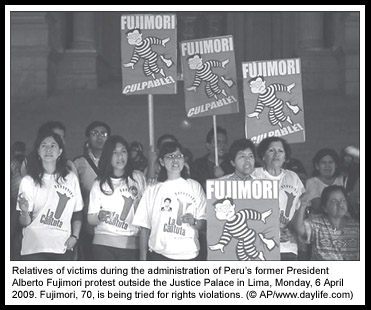

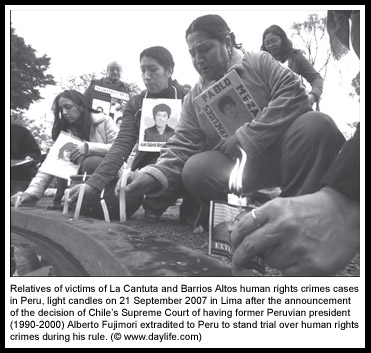

The Trial of Alberto Fujimori

In 2001, Fujimori was charged with corruption and

crimes against humanity and he was banned from holding public offices in

Peru until 2010. On 7 November 2005, he left Japan and travelled to Chile,

where he was arrested. Peru immediately lodged an extradition request,

which was initially rejected and then accepted on appeal by the Chilean

Supreme Court. In September 2007, Fujimori was extradited to Peru and his

trial begun on 10 December 2007 before a 3-judge panel of the Peruvian

Supreme Court (Sala Penal Especial de la Corte Suprema). Regarding human

rights abuses, Fujimori was accused for Barrios Altos massacre and La Cantuta case, as it was alleged that the

Grupo Colina death squad was

under his direct command. 12 Further, Fujimori was charged with ordering

the illegal detention and interrogation of a prominent journalist, Gustavo

Gorriti, and businessman Samuel Dyer, also in 1992. Since the beginning of

the trial, Fujimori rejected entirely the charges and claimed to be

innocent.

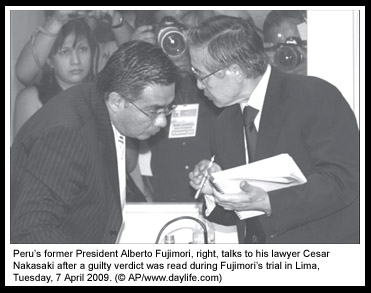

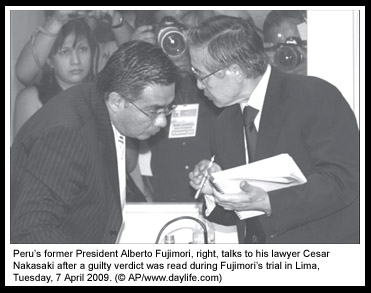

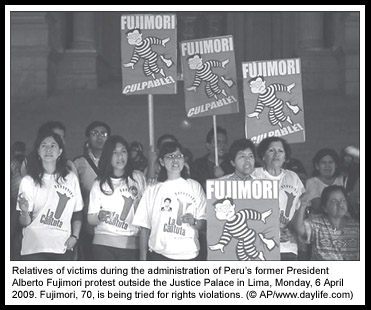

On 7 April 2009, the Chamber of the Peruvian Supreme

Court delivered an extremely detailed judgment 13 where Fujimori was found

guilty of command responsibility (autoría mediata) for aggravated murder

of 25 people, serious bodily harm and kidnapping. 14 Given that the

offenses were materially perpetrated by intelligence officers that

operated in the Grupo Colina, and that they were committed in the context

of a widespread practice, they were qualified as crimes against humanity.

In its judgment, the Court collected a significant number of testimonies

and the findings of the CVR as well as the judgments of the Inter-American

Court were taken as evidences.

The Court meticulously reconstructed the origin of the

Grupo Colina, which was set up in August 1991 and operated until the end

of 1992. It was composed of high-ranking intelligence officials (some of

whom appointed by Fujimori), who responded directly to Montesinos, whom,

in his turn, responded exclusively to Fujimori, meeting with him daily and

reporting to him about all details of intelligence operations. The

constitution of Grupo Colina must be contextualized in the overall

counter-insurgent strategy conceived by Fujimori (who, as a president, was

also the commander- n-chief of the army and the absolute head of the

intelligence services): he consciously decided to abandon the rule of law

and to selectively annihilate those deemed to be members of Sendero

Luminoso and MRTA instead of regularly arresting and giving them a fair

trial. In fact, Grupo Colina’s mission was not to arrest suspected

terrorists: the squad was meant to physically eliminate pre-selected

targets, by means of arbitrary killings, enforced disappearances and

massacres.

Fujimori planned such strategy of systematic human

rights violations, authorized it and, once public opinion

called for the clarification of the events, adopted all

measures to grant impunity (through, for instance, the use

of military tribunals and the enactment of the self-amnesty

laws) to Montesinos and the members of Grupo Colina. 15 As

mentioned, Fujimori was constantly informed by Montesinos

on the development of his ruthless intelligence strategy and,

in particular, he knew all details concerning Barrios Altos and La Cantuta operations.

Of particular interest is the fact that the Peruvian

judges agreed with the prosecutor in saying that Fujimori was responsible

for the crimes as “autor mediato” and not as a principal or an instigator

or an accomplice. This means that he bears primary active criminal

responsibility, as a perpetrator who has acted through an intermediary and

not as a superior whom, by omission, has failed to prevent the commission

of crimes perpetrated by his subordinates. According to the judgment, the

“autor mediato” actually commits a crime through another person, taking

advantage of his position over his subordinates in the context of an

organized power machinery. Fujimori was the apex of such organized power

machinery and those who materially perpetrated the crimes were mere

executors, who, in fact, were interchangeable (to Fujimori, it did not

matter who committed the act of killing or forcibly disappearing his

targets as long as the action was “successfully” finalized). Further,

executors were not necessarily aware of the overall strategy of all

details of the operations.

In order to reach such conclusions, the judges of the

Supreme Court had to be persuaded that:

• such organized power machinery existed and Fujimori

was at the top of it;

• Fujimori exercised absolute command over the said organized power

machinery;

• the organized power machinery was placed and acted outside the

control of the law;

• Fujimori could “use” different interchangeable material executors to

serve his purposes; and

• Material executors were highly likely and fully available to commit

the “necessary” crimes.

In the view of the jury, the testimony and documentary

evidence presented corroborated all mentioned requirements and Fujimori

was sentenced to 25 years in prison (until 10 February 2032, when he would

be almost 95-year old) and to the payment of pecuniary compensation to

cover damages caused to the victims and their relatives.

Another aspect of the judgment which vests great

importance to honor of the victims and to restore their dignity and that

caused genuine satisfaction among civil society and relatives of the

victims, is that the judges officially declared that it had been

established beyond reasonable doubt that none of the 29 people

disappeared, killed, kidnapped or seriously harmed in the events under

scrutiny was in any way related to the activities of Sendero Luminoso nor

a member of the latter. After more than 17 years of infamous hints, the

memory of 29 people was finally honored and truth re- stablished to the

advantage of their relatives and of society as a whole.

Fujimori’s representatives appealed the judgment,

claiming for its annulment. The First Transient Criminal Chamber of the

Supreme Court is in charge of handling the appeal and has a 4-month term

to deliver its verdict.

Conclusions

The judgment sentencing Alberto Fujimori to 25 years in prison

represents a historical victory of justice over impunity and it is highly

instructive precisely because it has been flawlessly conducted by a

domestic court. This shows that international tribunals must be considered

a complementary support (in particular, international mechanisms of

protection of human rights) and a last resort (international criminal

tribunals) to combat injustice. The fact that a former dictator is judged

by his country’s own judicial system concretely reaffirms the primacy of

law and brings cleansing and educational effects. All the more so when

also the other prominent figures of all the parties to the conflict (with

the notable exception of one of the leaders of MRTA that was arbitrary

executed by the army) have been captured, judged and sanctioned by means

of domestic fair trials.

Indeed, the cogent conclusions reached by the 3-judge

jury that condemned Fujimori come as a result of a long struggle and they

are based on a number of other initiatives of domestic, international and

transitional justice. In this case there has been a virtuous interaction

among these different levels, which has led to the carrying out of a fair

trial in its most appropriate venue and has also set a number of

fundamental references:

• military tribunals are competent only over offenses of a military

nature, committed by military personnel and can never judge over alleged

gross human rights violations; • people accused of grave human rights

violations cannot benefit from amnesties or similar measures; and

• a State in the territory under whose jurisdiction a person alleged to

have committed gross human rights violations is found, shall extradite

or surrender that person or submit the case to its competent authorities

for the purpose of prosecution.

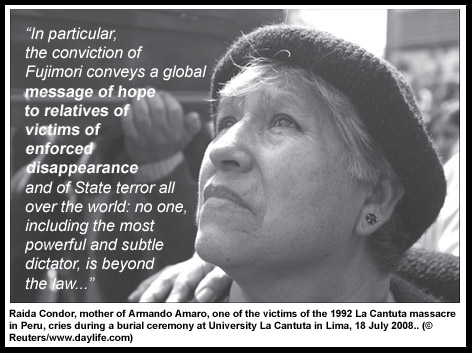

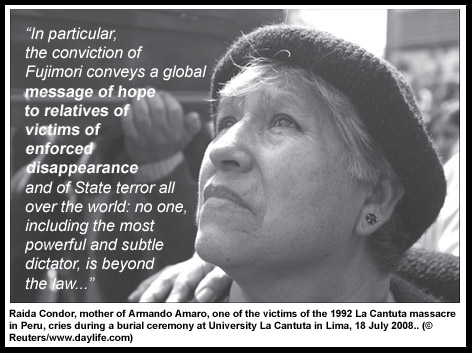

In particular, the conviction of Fujimori conveys a

global message of hope to relatives of victims of enforced disappearance

and of State terror all over the world: no one, including the most

powerful and subtle dictator, is beyond the law. Civil society and the

legal system are watching and are calling for ineluctable answers.

No matter how long this may take, truth must be

disclosed, justice served and memory restored and preserved.

____________________________

End notes:

1 For information on the CVR and the integral version of the final report

(in Spanish), see

http://www.cverdad.org.pe/.

2 See Final Report of the CVR, Lima, 2003, Tome VII, sections 2.22 (La Cantuta) and 2.45 (Barrios Altos).

3 The conclusions formulated by the CVR can be found, in the Spanish

version athttp://www.cverdad.org.pe/ifinal/conclusiones.php. For the

findingsconcerning Fujimori, seeparas.98-104.

4 Ibid., para. 100.

5 Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR), Case Chumbipuma Aguirre

and others (Barrios Altos) v. Peru, judgment of 14 March 2001, Ser. C No.

75.

6 Ibid., para. 41.

7 Ibid., para. 43.

8 Ibid., para. 44.

9 IACHR, Case La Cantuta v. Peru, judgment of 29 November 2006, Ser. C.

No. 162.

10 Infra, para. 4

11 IACHR, Case La Cantuta, supra note 9, para. 160.

12 It is worth noting that 24 alleged members or accomplices of

Grupo

Colina have been arrested and are currently under trial. 13 have already

been convicted for slaughter.

13 The integral version of the judgment, in Spanish, can be found at:

http://www. gacetajuridica.com.pe/noticias/sentencia-fujimori.php.

14 Although the Court referred to “enforced disappearances” committed by

Grupo Colina all through the text of the judgment, it did not find

Fujimori guilty of such crime as, when the events took place, enforced

disappearance was not codified as an autonomous offense under Peruvian

criminal code.

15 The kidnappings of Gustavo Gorriti and Samuel Dyer were carried out as

a part of the mentioned systematic practice as both were considered

“troublesome” by Fujimori who, accordingly, ordered their abduction and

their interrogation in the basements of the headquarters of the Military

Intelligence Service by members of the Grupo Colina. Both Gorriti and Dyer

testified at the trial against Fujimori.

From 1980 to 2000, Peru was ravaged by a bloody

internal armed conflict whose principal actors were on the one hand the

two guerrilla movements known as Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso)

and Movimiento Revolucionario Tupac Amaru (MRTA) and, on the

other, the Peruvian government, backed by self-defense groups of peasants

(rondas campesinas) and paramilitary groups created by the

intelligence service, such as the notorious Grupo Colina and

Comando Rodrigo Franco.

From 1980 to 2000, Peru was ravaged by a bloody

internal armed conflict whose principal actors were on the one hand the

two guerrilla movements known as Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso)

and Movimiento Revolucionario Tupac Amaru (MRTA) and, on the

other, the Peruvian government, backed by self-defense groups of peasants

(rondas campesinas) and paramilitary groups created by the

intelligence service, such as the notorious Grupo Colina and

Comando Rodrigo Franco.

The application concerning Barrios Altos massacre was

submitted to the Court while Fujimori was still in power and he pretended

to withdraw the acknowledgement of the competence of the Court to escape

international scrutiny. Such withdrawal was rejected by the Inter-American

Court. While the case was pending before the latter, Fujimori fled the

country. The transitional government declared null the attempt of

withdrawal of the competence of the Court and recognized its international

responsibility for the violation of Articles 4 (right to life), 5 (right

to humane treatment), 8 (right to fair trial), 25 (judicial protection) in

conjunction with Article 1.1 (obligation to respect rights) of the

American Convention on Human Rights. On 14 March 2001, the Inter- American

Court rendered a landmark judgment, accepting the acknowledgement of

international responsibility and, at the same time, affirming a key

principle in the struggle against impunity.5 Referring to the enactment of

the 2 self-amnesty laws, the Court considered that:

The application concerning Barrios Altos massacre was

submitted to the Court while Fujimori was still in power and he pretended

to withdraw the acknowledgement of the competence of the Court to escape

international scrutiny. Such withdrawal was rejected by the Inter-American

Court. While the case was pending before the latter, Fujimori fled the

country. The transitional government declared null the attempt of

withdrawal of the competence of the Court and recognized its international

responsibility for the violation of Articles 4 (right to life), 5 (right

to humane treatment), 8 (right to fair trial), 25 (judicial protection) in

conjunction with Article 1.1 (obligation to respect rights) of the

American Convention on Human Rights. On 14 March 2001, the Inter- American

Court rendered a landmark judgment, accepting the acknowledgement of

international responsibility and, at the same time, affirming a key

principle in the struggle against impunity.5 Referring to the enactment of

the 2 self-amnesty laws, the Court considered that: On 29 November 2006, the Inter-American Court rendered

a judgment on La Cantuta case which was based to a large extent on the

findings of the CVR.9 The representatives of Peru partially acknowledged

the international responsibility of the State for the violation of

Articles 3 (right to juridical personality), 4 (right to life), 5 (right

to humane treatment, with regards to the material victims of the case), 7

(right to personal liberty) in conjunction with Article 1.1 (obligation to

respect rights) of the American Convention. The Court deemed it

appropriate to further clarify certain aspects of the case. First, it

found that Article 5 of the Convention had been violated not only with

regards to the direct victims of the case but also to their relatives,

whose mental and moral integrity were impaired as a direct consequence of

the events. The Court found also a violation of Articles 8 (right to a

fair trial) and 25 (right to judicial protection) in connection with

Article 1.1 of the Convention. It declared that the proceedings before the

military jurisdiction did not respect the international standards of the

fair trial and that the application of the 2 self-amnesty laws to the case

was contrary to the American Convention and, in particular, amounted to a

violation of Article 2 (domestic legal effects) of the American

Convention. While expressing appreciation for the resuming of trials

before ordinary courts on the case of La Cantuta in 2001, the Court found

that Peru had exceeded any reasonable delay. The Court pointed out that

the facts of La Cantuta were to be seen as part of a systematic practice

of enforced disappearances and extra-judiciary executions perpetrated by

State agents and paramilitary groups. This amounted to a crime against

humanity and a gross violation of ius cogens.

On 29 November 2006, the Inter-American Court rendered

a judgment on La Cantuta case which was based to a large extent on the

findings of the CVR.9 The representatives of Peru partially acknowledged

the international responsibility of the State for the violation of

Articles 3 (right to juridical personality), 4 (right to life), 5 (right

to humane treatment, with regards to the material victims of the case), 7

(right to personal liberty) in conjunction with Article 1.1 (obligation to

respect rights) of the American Convention. The Court deemed it

appropriate to further clarify certain aspects of the case. First, it

found that Article 5 of the Convention had been violated not only with

regards to the direct victims of the case but also to their relatives,

whose mental and moral integrity were impaired as a direct consequence of

the events. The Court found also a violation of Articles 8 (right to a

fair trial) and 25 (right to judicial protection) in connection with

Article 1.1 of the Convention. It declared that the proceedings before the

military jurisdiction did not respect the international standards of the

fair trial and that the application of the 2 self-amnesty laws to the case

was contrary to the American Convention and, in particular, amounted to a

violation of Article 2 (domestic legal effects) of the American

Convention. While expressing appreciation for the resuming of trials

before ordinary courts on the case of La Cantuta in 2001, the Court found

that Peru had exceeded any reasonable delay. The Court pointed out that

the facts of La Cantuta were to be seen as part of a systematic practice

of enforced disappearances and extra-judiciary executions perpetrated by

State agents and paramilitary groups. This amounted to a crime against

humanity and a gross violation of ius cogens. The Court ordered Peru to investigate, judge and

sanction those found to be responsible for the violations, to pay

pecuniary compensation to the relatives of the victims, to carry out the

exhumations and to identify and deliver to the relatives of the eight

disappeared people their mortal remains, to issue an apology in a public

ceremony and to honor the memory of the victims, to provide free medical

and psychological treatment to the relatives of the victims, to publish

relevant abstracts of the judgment in the official gazette of the country

and to establish a program of education on human rights and international

humanitarian law for public officials.

The Court ordered Peru to investigate, judge and

sanction those found to be responsible for the violations, to pay

pecuniary compensation to the relatives of the victims, to carry out the

exhumations and to identify and deliver to the relatives of the eight

disappeared people their mortal remains, to issue an apology in a public

ceremony and to honor the memory of the victims, to provide free medical

and psychological treatment to the relatives of the victims, to publish

relevant abstracts of the judgment in the official gazette of the country

and to establish a program of education on human rights and international

humanitarian law for public officials.